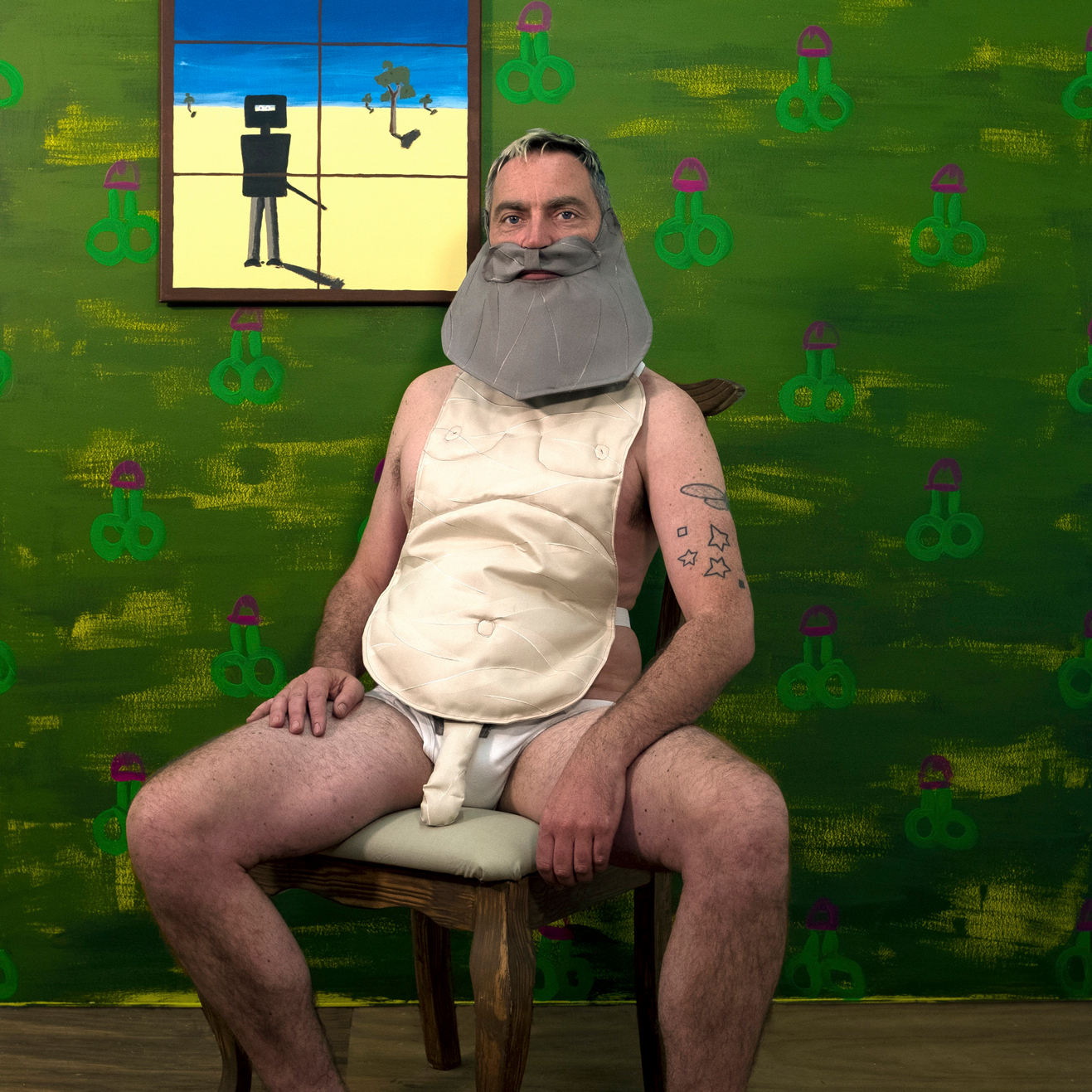

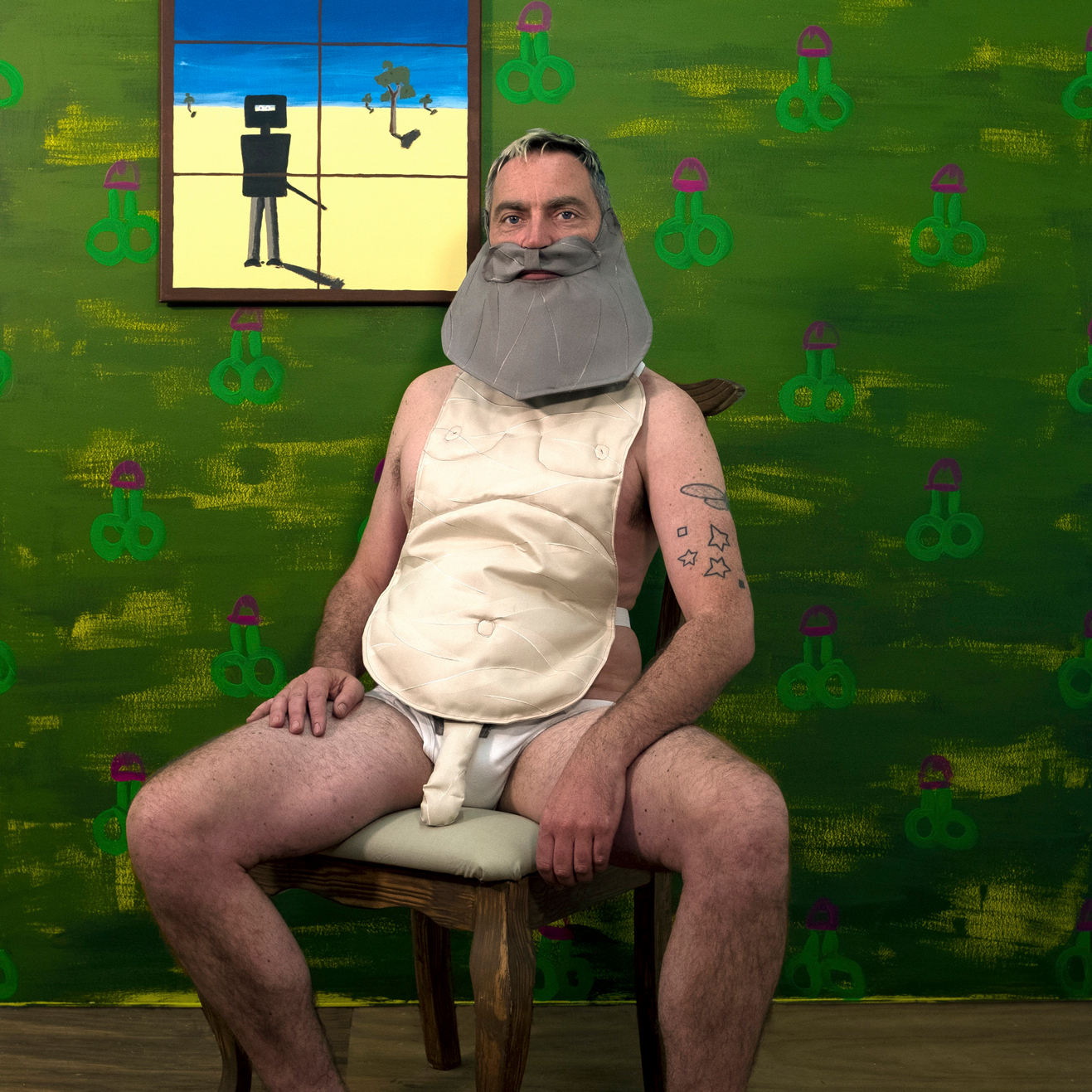

840 x 594mm. Inkjet prints on archival rag.

These vignettes are a collision between my interest in Captain Moonlite, the Australian bushranger, and Sidney Nolan’s 1946-47 series of paintings depicting Ned Kelly.

There were no queer heroes in regional Victoria in the 1970s and 80s, the era when I grew up. None from the past, none in the present… and a future queer hero was unimaginable. The stuff of legends was the domain of real men, not closeted teenagers.

The bushranger, Ned Kelly, was a real man. The pervasive image of Kelly is one of an underdog standing up to injustice and challenging authority, a man who was hounded to the gallows by a prejudiced constabulary; the quintessential larrikin, an Australian icon and romantic myth. The painter Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series of 1946-47 was a major artistic contribution to the mythologizing of the bushranger. Apparently, Nolan empathised with Kelly because he drew parallels with emotionally complicated events in his own life. He said the paintings were secretly about himself.

The novelist Peter Carey says that most Australians know some of the history of Ned Kelly, and to fill the gaps we “invent and make-up stories.” So, what about my need for a queer historical hero – the queer equivalent of Kelly?

Andrew George Scott, known as the bushranger Captain Moonlite, was hanged for his crimes in 1880 in Sydney. Moonlite gained notoriety when he and his gang had a shootout with police at Wantabadgery Station near Wagga Wagga in NSW. During the gunfire, Moonlite’s second in command, James Nesbitt was fatally shot.

There has been a lot of research into the life of Captain Moonlite in recent years. Based on eyewitness accounts of his anguish at Nesbitt’s death, and his later prison correspondence, it’s clear the two men were lovers. Australia’s history includes a queer bushranger!

Bushrangers and Buggery is a contribution to the creation of a mythology based on Captain Moonlite. Moonlite and Kelly were contemporaries, and undoubtedly knew of each other (Moonlite’s gang were at times mistaken for the Kelly Gang). What if the two bushrangers met? Who is to say they didn’t?

The series of vignettes that make up Bushrangers and Buggery, playfully explores this idea and proposes a historical narrative that is only as truthful as I, the queer storyteller, want it to be. I get my own bushranger to empathise with, and create a series of my own that is (not so secretly) about myself.